‘The Church of England should blame the death of my brother’

BBC

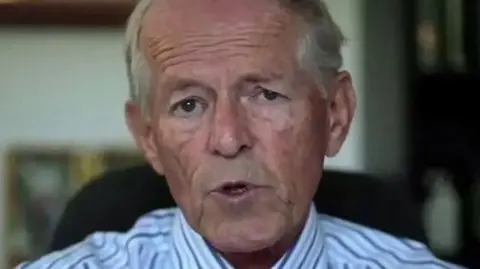

BBCThe sister of a 16-year-old boy who drowned while swimming naked at a Christian holiday camp in Zimbabwe run by child abuser John Smyth blames the Church of England for his death.

“The Church could have abused John Smyth. They should have stopped him. If they had stopped him, I think my brother [Guide Nyachuru] he would still be alive,” Edith Nyachuru told the BBC.

A British lawyer had moved to Zimbabwe with his wife and four children from Winchester, England in 1984 to work with an evangelical organization.

This happened two years after an investigation revealed that he was abusing boys in the UK, most of whom he had met at Christian rest camps run by a charity he chaired linked to the Church, in painful physical, mental and sexual abuse.

A 1982 report, prepared by Anglican priest Mark Ruston, about these sticks said “the extent and severity of this practice was horrific”, there are reports of boys being beaten so hard that they were tied up, one explains that they had to wear diapers until the wounds burst. over.

Despite these shocking revelations, mostly involving boys from Britain’s elite public schools, Rushton’s report was not widely circulated.

Ten years later, at the age of 50, Smyth had established himself as a respected member of the Christian community in Zimbabwe. He has since set up his own organization, Zambesi Ministries, with funding from the UK – and has been handing out similar punishments at marketing camps in the country’s top schools.

Ms. Nyachuru says her brother’s trip was a Christmas morning gift to another sister who took one of Smyth’s booklets and was impressed with everything that happened this week.

Looking at an old photo of Guide, he says he was the youngest of eight siblings, and an only boy: “He was loved by everyone.”

“A lovely boy… The guide was to be made head the following year,” he recalled, adding that he was “a smart boy, a good swimmer, strong, healthy with no known medical conditions”.

But within 12 hours of being taken out of the camp at Ruzawi School in Marondera, 74 kilometers away from the capital, Harare, on the night of 15 December 1992, the family received a phone call reporting that he had died.

Witnesses said that like all the boys, the Guide had gone naked in the pool before going to bed – a camp tradition. The other boys returned to the lodge, but the Guide’s absence was not noticed – which his sister found surprising – and his body was found at the bottom of the lake the next morning.

Her family rushed to the mortuary but Mrs. Nyachuru’s shock was caused by confusion when the police prevented her from seeing her body: “He told me: ‘You can’t go in there because you are dressed inappropriately.’

“My father, brother-in-law and our teacher came in and put him in a box.”

Nudity seems to be something that Smyth was groomed for in his camps. Those who attended the camp shared that he used to wander around naked in the boys’ quarters – where he also slept, unlike the other workers.

He used to shower naked with them in the trees together and the boys were ordered not to wear underwear in bed.

“He promoted nudity and encouraged boys to go naked in the summer camp,” a former student who attended the Ruzawi camp in 1991 told the BBC.

But his sense of humor put many at ease, he said.

“Smyth was very friendly, laid back, approachable, really nice, always joking around.

“Smyth was walking around the bedrooms and the bathroom wearing nothing but a towel slung over his shoulder.”

The reason given for the no-underwear rule in the evenings was “because it would enlarge them,” he recalled.

Smyth made speeches about masturbating, sometimes led nude prayers and encouraged trampling on naked people, an activity he described as “flappy banging” – all behavior noted in an investigation by Zimbabwean attorney David Coltart that began in May 1993.

It was the slaps that Smyth gave to the boys who were infamous with the table tennis bat, called “TTB”, that led the parent to the door of Coltart, who worked in the law office in Zimbabwe’s second largest city, Bulawayo.

He wanted to know why one of his sons had come back from holiday camp with bruises on his buttocks so much so that he took him to the doctor, who found a “12cm x 12cm bruise”.

“He saw this and wanted to know what happened and it turned out that his son had been badly beaten naked, he came to me to ask for advice,” Coltart, who is now the mayor of Bulawayo, told the BBC.

“When I heard that this is a Christian organization – I am an elder in the Presbyterian Church – I contacted my pastor and we contacted the Baptist Church Methodist Church and two other churches in the city and I taught those churches to investigate this matter,” he said.

44-year-old Jason Leanders, who entered the camp soon after Mhlandlela’s death, said he was beaten three or four times a day by Smyth, who would put his hands down his pants to check he hadn’t put on extra layers. to hide the buttocks.

“My bum was black,” she told the BBC. “But since you’re a boy, you work hard.”

For many boarding school students, beatings were considered “normal”, former Zimbabwean cricketer Henry Olonga, who attended the night Guide camp where he died, said in his 2015 autobiography.

But after Coltart was able to track down Rushton’s report, the gravity of the problem became apparent. He wrote to Smyth instructing him to immediately set up the Zambesi Ministries camps.

“It was calculated, he focused on the boys, he trained the young men.

But Coltart’s partnership with Smyth was strained.

“He was a man who knew how to speak and was very aggressive in the meetings I had with him. He used all his skills as a judge to intimidate. He was older than me. At the time I was a junior lawyer at 30 years old. He used the fact that he was an English QC [Queen’s Counsel].”

Rather than go along with Coltart’s various requests, he doubled down in a letter to parents before the August 1993 camps, describing himself as a “camp dad” and defending nudity and beatings, writing: “I’ve never been a boy, but I play table tennis when I have to… although most consider TTB (as as it is known) as a joke.”

In this case it seems that there is no concealment of beatings as “spiritual behavior” as was the case in the UK. He also admitted to Coltart that he took nude photos of the boys, but said they were “from the shoulders up” for publicity purposes.

Coltart consulted two psychologists about his findings, both of whom advised that Smyth should stop working with children.

His 21-page report was then published in October 1993, and distributed to the principal teachers and church leaders in Zimbabwe.

“The report was not widely published, recognizing the risk of a defamation lawsuit,” Coltart said.

However, it “stopped him from Zimbabwe” as private schools were his breeding grounds, he said. Zambesi Ministries camps continued in some form, but not in schools or under Smyth’s leadership

Coltart then instructed another law firm to proceed with the case against Smyth who was eventually charged with involuntary manslaughter for Guide’s death, as well as charges related to the assault.

But, according to former BBC TV producer Andrew Graystone in his 2021 book about the torture, the case was full of problems, the police records were missing and Smyth’s legal strictness led to the removal of the prosecutor – one was not appointed, so the case was officially closed in 1997.

Ms Nyachuru says no post-mortem took place at the time – Mhlahlandla was buried the day she drowned at her home, with Smyth officiating.

Following Coltart’s report, Smyth faced deportation to Zimbabwe but Graystone says he used his vast connections to avoid this, lobbying various Cabinet ministers – some of whose sons attended his camps – with suggestions that even the then President Robert Mugabe was contacted by one of Smyth’s allies.

But since the time of Smyth’s prosecution, the family has been granted temporary residence permits, which had to be renewed every 30 days.

In 2001, after spending a long time outside the country on tour, Smyth and his wife Anne were denied re-entry, prompting them to move to the South African coastal city of Durban and a few years later to Cape Town, where the couple was based. living when the Church of England became fully aware in 2013 of the abuses he had committed in the UK.

“The Anglican church in Cape Town where John Smyth was serving… has reported that it has never received reports that he abused or trained young people,” said Thabo Makgoba, the archbishop of Cape Town, in a statement in response. this week’s resignation of Justin Welby as Archbishop of Canterbury.

Smyth was excommunicated only a year before his death in 2018, after he was publicly denounced as an abuser in a Channel 4 News report.

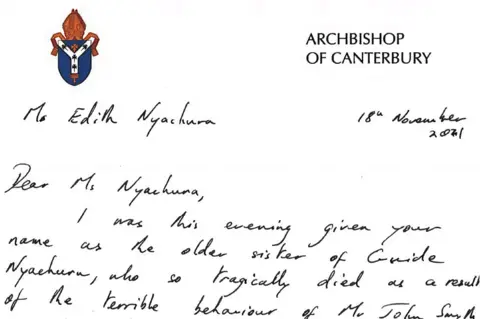

Ms Nyachuru told the BBC that it was not until 2021 that she received a written apology from Welby over her brother’s death, in which he admitted that Smyth was responsible and that the church had failed his family.

He wrote back describing the apology as “too little, too late” and is now asking other senior church leaders who failed to intervene to prevent Smyth’s abuse: “I think the people of the church, if they see something is wrong. the right way, if it needs the police they should go to the police.”

Coltart believes that the church is not the only one to blame, and suggests that other institutions in the UK must face their failure to warn Zimbabweans.

He recommended Makin’s Church of England reportthey say “it leaves nothing”. The report says that about 85 boys and young men were abused in African countries, including Zimbabwe.

Coltart encouraged the Church to reach out to them.

“I think it is possible that there are still traumatized people in Zimbabwe, maybe in South Africa, suffering from PTSD and I think the Church of England has a responsibility to see those people and to give them the medical help they may need,” he said. .

Mr Leanders says many friends “are still so traumatized by the beating that they don’t even want to talk about it”.

“Smyth was protected in England and protected in Zimbabwe. The protection went on for too long and deprived the victims of the opportunity to deal with Smyth as adults.”

Additional reporting from the BBC’s Gabriela Pomeroy.

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBCSource link